To Love is To See: an Ash Wednesday Sermon

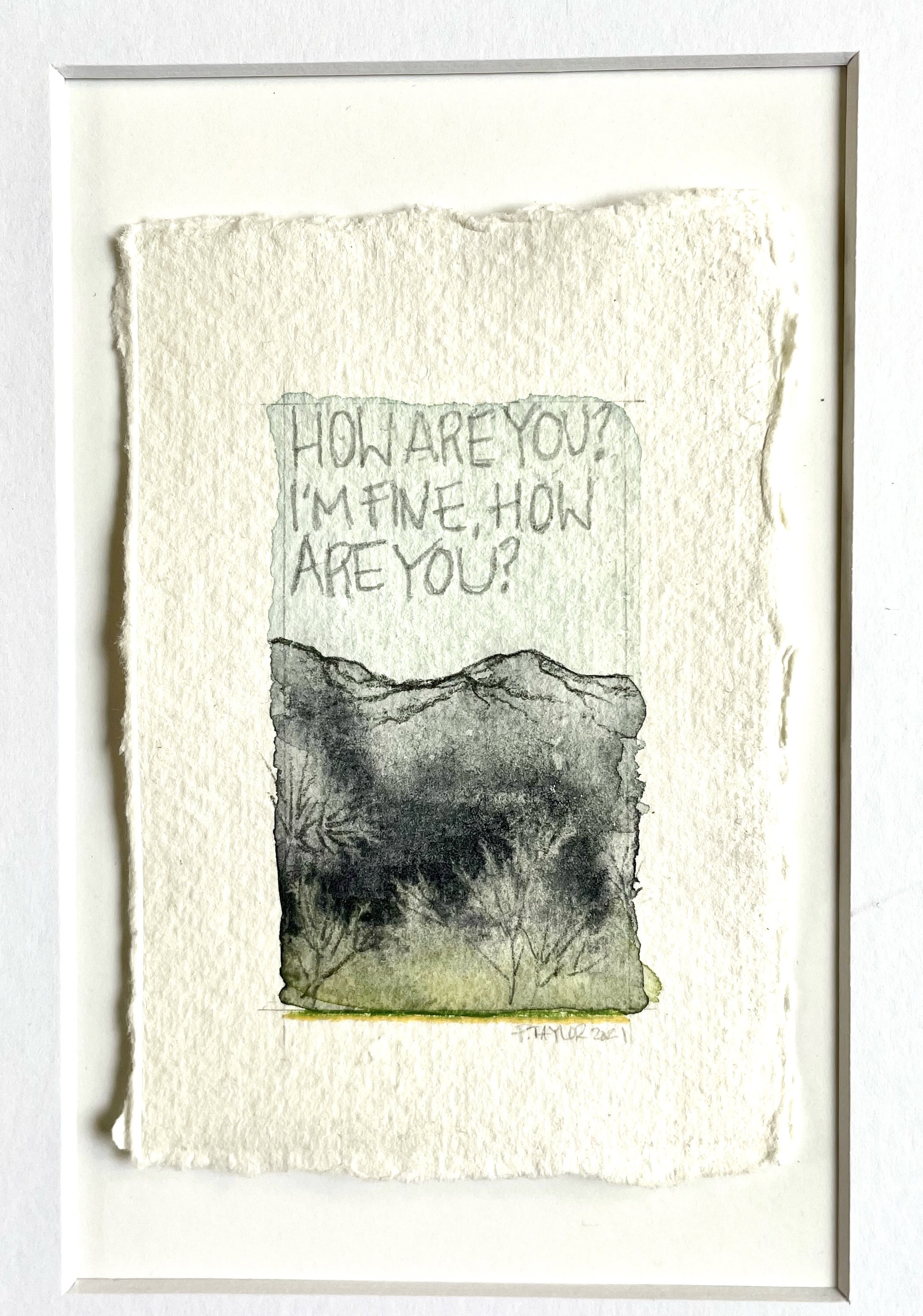

Phaedra Taylor, “The Things We Say” (2023)

(I began my Ash Wednesday homily at Church of the Cross by reading an excerpt from Frederick Buechner’s essay, “To see is to love, to love is to see,” in his book, The Remarkable Ordinary.)

What does it mean to see each other in love? And what does that have to do with our journey through Lent? Those are the two questions that I would like to answer in this short homily.

Allow me to suggest to you, in answer to the first question, that to see each other in love is quite simply to see each other as Jesus sees us: which is to say, to borrow language from that marvelous TV show, “Friday Night Lights,” with clear eyes and a full heart.

In seeing us with clear eyes, Jesus does not pretend that we are anything but the broken creatures that we are—often selfish, at times petty or jealous, frequently judgmental, many times fearful and plenty insecure. But in seeing us with a full heart, Jesus sees us with a kind of love that exceeds all requirements and he extends his inexhaustible grace to us in our hour of need because it is his everlasting pleasure to do so with people like us, broken but beloved.

“To see is to love and to love is to see,” writes Frederick Buechner. Jesus, of course, shows us what that means. He sees people in love and he loves them by seeing them, really and truly seeing them.

He sees Peter in his brutish ways, running people over by the strength of his overbearing personality.

He sees James and John, how their intemperate zeal causes them to want to rain down hate on those who have rejected Jesus.

He sees Judas in his obsessive anger against the Romans, a kind of anger consumes and distorts him from the inside out.

He sees Martha. He sees how she is paralyzed by her anxiety and blind to what would actually be good for her in the moment.

He sees Nicodemus in his Pharisaical cowardice.

He sees Zacchaeus in his shame.

In Luke 7, Jesus sees the widow crying for her dead son and, the text tells us, “his heart goes out to her.”

In John 11, Jesus sees Mary weeping and he weeps with her.

In Luke 8, he sees the woman with the issue of blood—he sees her in utter helplessness and he does not stop her from being seen by a crowd of people whose instinct would be to shun and shame her. But Jesus does not shame her. He does not shun her. He sees her in love.

Jesus sees that we too are like the people that he encounters all throughout the gospels: defensive, despairing, lost, tired, weak. And as with all those people, he too sees us in love. He sees that we are like sheep without a shepherd. He sees that we are broken by the cruelties of this world. He sees that we are but dust, frail and so very incapable of saving ourselves.

He sees us in love and he also invites us to see each other in love, which is of course easier said than done. In some cases, we do not wish to be seen in such a way.

(You can listen to the rest of the sermon here.)

(The artwork is from a new series by my wife Phaedra Jean Taylor: “The Things We Say" [But Don’t Really Believe]).

"Christ in the House of Martha and Mary," by Johannes Vermeer, before 1654–1655, oil on canvas

"Jesus Raises the Widow's Son at Nain," by Johann Zick (1752)

Initial D (Zacchaeus and Christ). Hildesheim, probably 1170s. Tempera colors, gold leaf, silver leaf and ink on parchment, 11.1 x 7.4 inches

“Kiss of Judas” (1304–06), fresco by Giotto, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

“Study for Nicodemus Visiting Jesus,” by Henry Ossawa Tanner (1899)