The Memory of Touch

My aunt Grace, my father’s only sibling, died on April 30, 2020, at the age of 81. She passed in the hospice-care home where she had spent the final six years of her struggle against Alzheimer’s disease.

Because her death had occurred during the period of social isolation that COVID-19 required of us, no in-person funeral would take place.

My aunt, in fact, had wanted no flowers or fuss. She had wanted only to be left alone at her passing.

But for us as her family, locked down in our homes across the city of Austin, Texas, hundreds of miles away from Decatur, Georgia, we had not wanted to be left alone in our grief.

We had wanted something—anything—to process the awful fact of a death in our family. But that was not to be. My aunt got her wishes.

No liturgy would bear witness to the sound of voices singing their lament. There would be no hugs to absorb the sorrow, no hands to hold our grief, no casket to touch. No earth would be dropped into the grave, carved out of the Georgia red clay, where we might have heard the words:

“Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”

My aunt Grace reading Scripture at my grandma’s funeral in 2006.

If it is true that touch has a memory, as the poet John Keats once observed, what will our family be unable to remember about my aunt’s life, or our own, on account of this missing liturgical rite?

What emptiness will always haunt our memory of her?

What wound will never be healed?

What, in the end, will we lose because no corporate body bore witness to death’s sting in the corporeal form of Grace Taylor Ihrig and to Christ’s defeat of that painful sting in a liturgy for the burial of the dead?

Our experience, of course, was far from unusual.

The coronavirus pandemic that brought the world to a sudden halt in the spring of 2020, demanding that people shelter in place, involved a massive rupture of our common and communal life.

Among other things, it profoundly affected the embodied worship of the church.

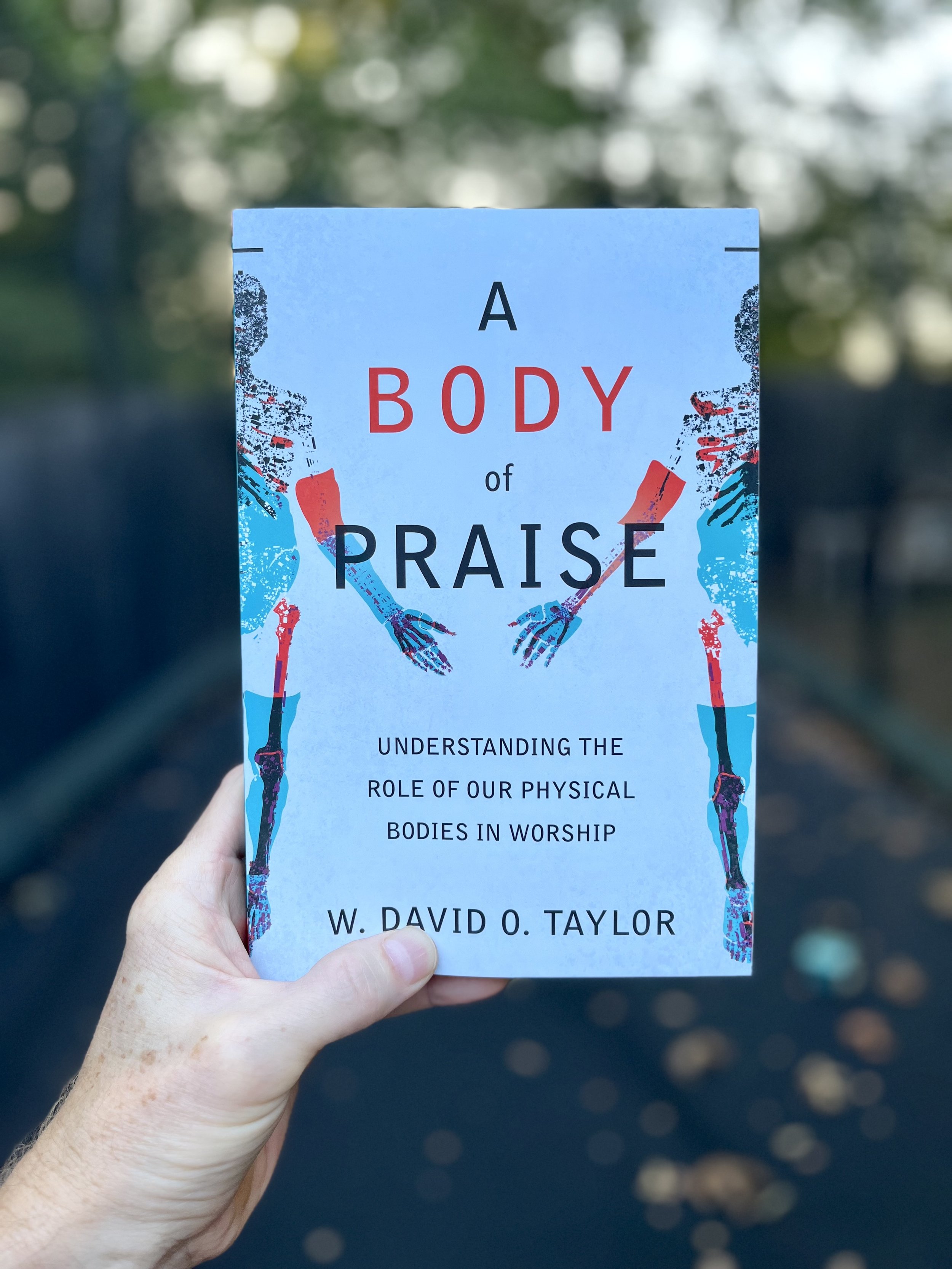

I explore at length what this means in my book, A Body of Praise, and I suggest that our bodies matter far more to our total wellbeing than many of us might be willing to conceive.

Our bodies are always talking. But are we willing to listen?