Hopkins’ Haecceity

I’ve decided to make the nineteenth-century Jesuit poet-priest, Gerard Manley Hopkins, my primary conversation partner in the introduction to my book on the vocation of artists.

Everything that I’m trying to say about what makes the work of artists unique is beautifully exemplified, it seems, in Hopkins’ sacramental theology and visceral, musical poetry.

Catherine Randall summarizes Hopkins’ theology this way: “Gerard saw nature as one exceedingly privileged venue for the revelation of God.”

The world of the senses, for Hopkins, served as a primary vehicle for making positive sense of the spiritual world. “Trees were presences to him, stars no mere luminaries but celestial sign posts; birds, divine emissaries and figures of God.”

But it’s not simply that matter bore witness to the immaterial. It was that the aesthetically dense media of art could say things about God and the world that prose could not—or not as well, at least.

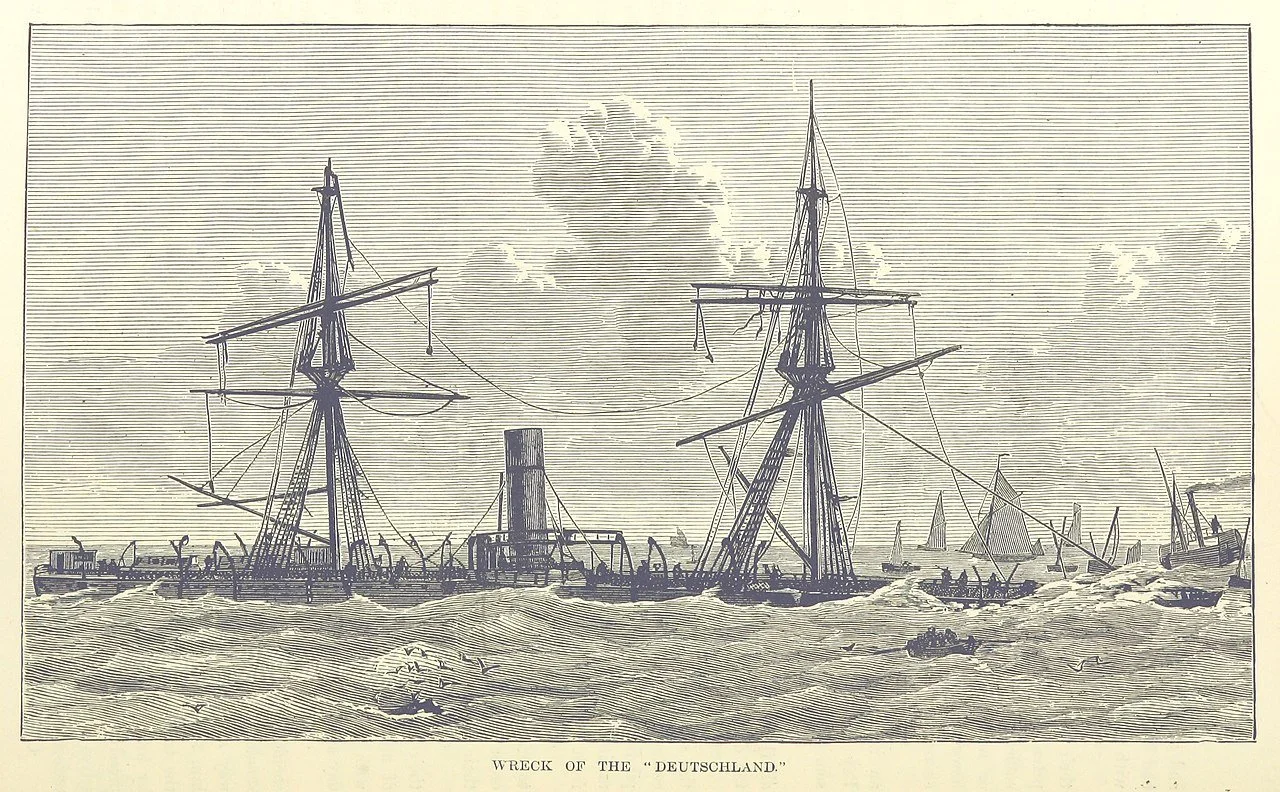

The incoherent character of natural evil, for example, witnessed in the shipwreck of the SS Deutschland in 1875 and which Hopkins found deeply disturbing, could be given coherent shape through the “primal stew of sounds and rhythms that, when he later went to Wales, boiled over into an intoxicating broth of Celtic music and evocative wordplay.”

Wiry and white-fiery and whirlwind-swivellèd snow

Spins to the widow-making unchilding unfathering deeps.

The senseless violence of the wreck and the tragic human losses that it caused was made more “sensible” through “a volatile phonetic event,” in Randall's words, in the form of a thirty-five-stanza epinicion ode.

What Hopkins offers to all artists, I suggest, regardless of their particular medium of art, is a theological vision that frees them to immerse themselves fully in the stuff of sensory, imaginative and affective matter—that is, the basic stuffs of art making.

What he offers also is permission to be fully themselves, their one-of-a-kind particular selves, what Hopkins called their haecceity, or “thisness,” borrowing from the thirteenth-century Franciscan philosopher, Duns Scotus—in God, through Christ, by the Spirit. As Hopkins puts it in his poem, “As Kingfishers Catch Fire”:

“Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.”

This book is going to be a great adventure, to be sure.

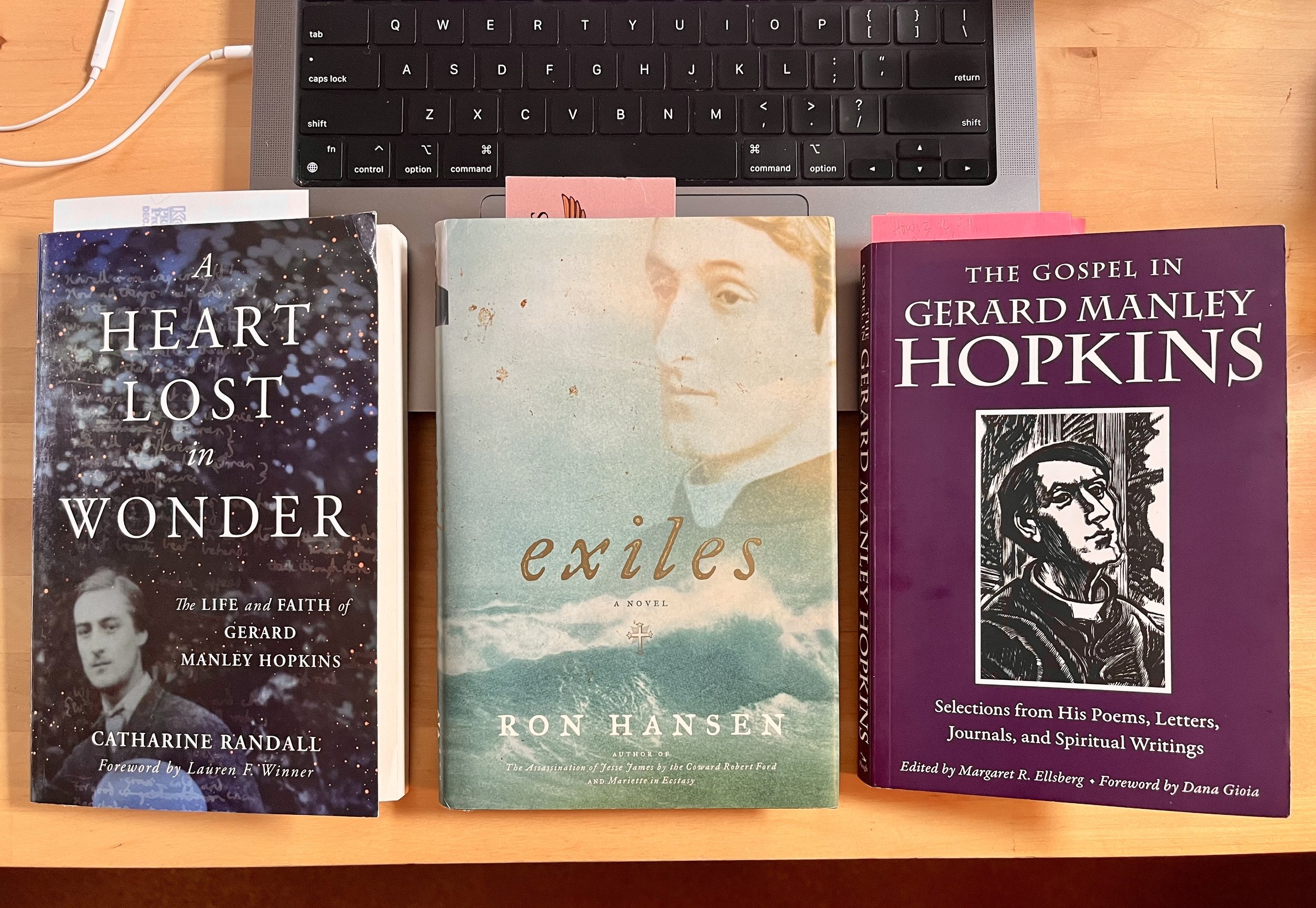

(PS: Catharine Randall’s book is an accessible introduction to Hopkins’ life and work. Margaret Ellsberg’s edited volume is a focused treatment to four poetic and theological themes in his work. Ron Hansen’s historical fiction novel is a poignant take on Hopkins’ response to the wreck of the Deutschland, in particular to the harrowing death of five German nuns, exiles from their homeland on their way to St. Louis, Missouri)

An 1887 illustration of the wreck of the SS Deutschland.

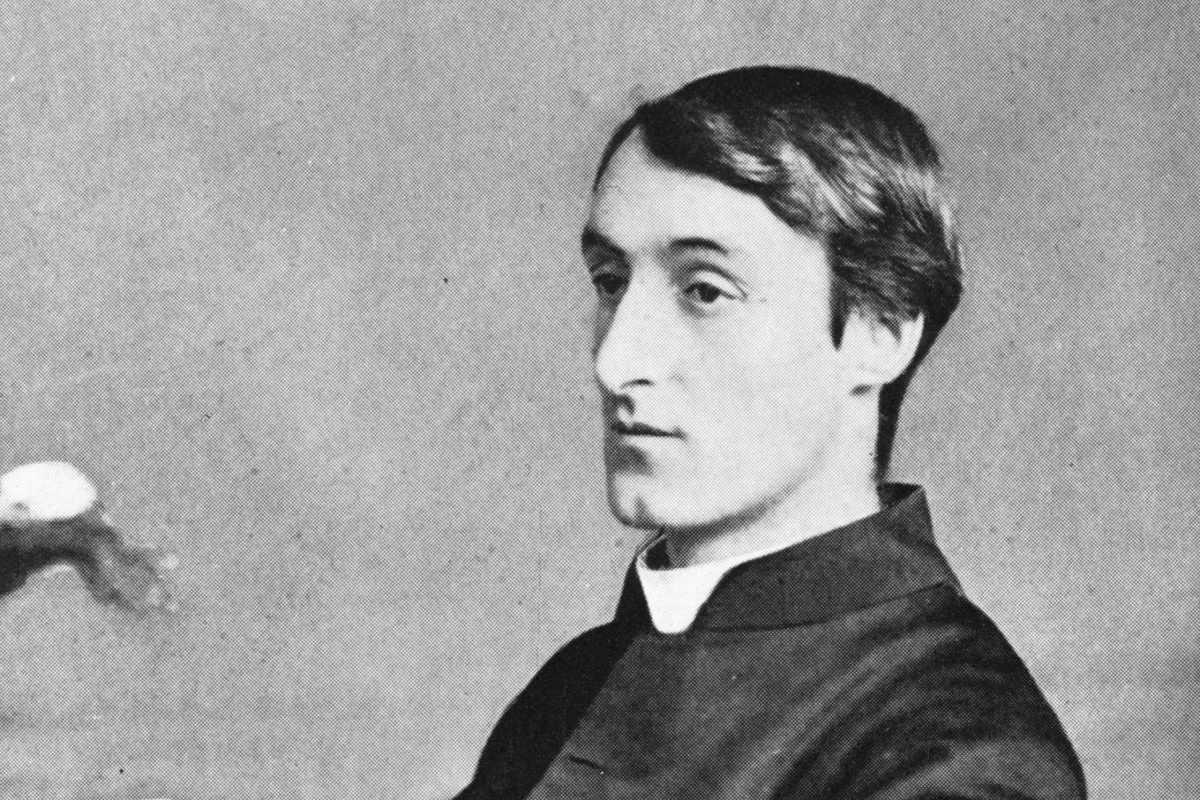

Hopkins at his desk, 1880 (age 36).

Hopkins with other Jesuits, Ireland, mid-1880s (front row, 4th from right).